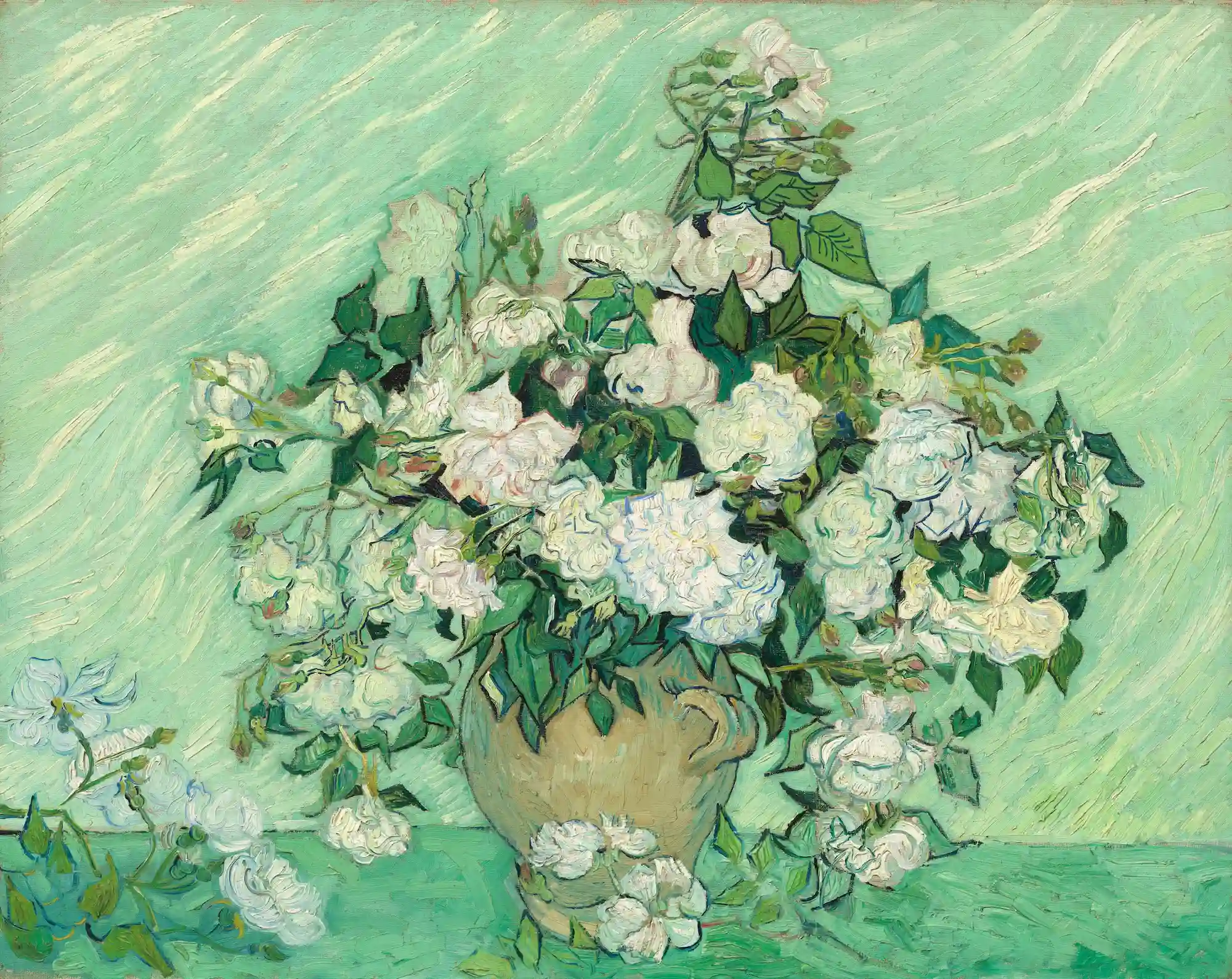

Roses, by Vincent van Gogh

Any Other

My parents knew that ten percent of my cells were missing an X-chromosome before I was born. I didn’t find out until I was nine. I had to start seeing a specialist, so I guess they couldn’t put off telling me any longer. At the time, it seemed like the most pressing issue I would face on account of this condition was not my height or kidney function or issues with my heart, but whether I’d be able to have children.

Names are one way to seize some sense of control in a world that offers us so little of it. I was almost a Lucinda, but my dad didn’t like the idea of people calling me Lucy. I don’t know what was so distasteful about that nickname, but he felt strongly enough to veto Lucinda. Just on the assumption – the possibility – that I’d want to shorten the name. Or that other people would shorten it for me. My mum, too, had a thing about nicknames (for Kristen, at least). I was told I shouldn’t let anyone call me Krissy, or Kris, or Kristy. And I took that to heart. I learned to hate all of them – the way they felt like a denial of who I was. Who I wanted to be. Who I was meant to be.

I’ve learned to embrace the relief of diagnoses – any answer, any label – over time. Even if they show you something shattering, seeing it is less terrifying to me than the mystery. The waiting. I remember going to multiple pediatric endocrinologists that first year, trying them out like therapists, interviewing each of them. One was an older woman who played the cello. When we met her, she was carrying it with her through the hospital corridors to her office. A cello doesn’t work when it’s missing a string, can’t create a vast number of the notes it should be able to. But it’s still a cello – would still be a cello, I guess.

I was bitterly disappointed, when I reached that age where names and their connotations become fascinating to kids, that my name didn’t have a more obscure, romantic meaning. A secret symbolism. Kristen. Christian. A Christian. A follower of Christ. As an added blow, my middle name was also devoid of any hidden layers. Victoria. Victory. A victor. Clear-cut. No room for interpretation. Transformation. Revelation. No room to fail without shame. But we all grow into our names, I think, with enough time. It seems like a means of survival, the only way to thrive in the circumstances we’re given. But surviving and thriving are two very different things, and I still struggle to discern exactly where the line between the two is. Does such a line – a measure of what we should be willing to endure, a measure of what’s worth enduring – even exist?

I forget how old I was when my mum first told me that she had two miscarriages before I was born. I know I was young. Maybe even younger than nine – before I knew I would inevitably have the same kinds of struggles (or even greater struggles) getting pregnant that my mother did. I wonder a lot about what getting the results of my amnio must have been like after losing two pregnancies already – if there was an impulse, however brief, to want to end the pregnancy, and how much the decision to keep me was based on bad odds. Relief mixed with its own kind of disappointment. I guess this is the baby we get. My mum also told me, more recently, that she had a prayer group put their hands on her when she was hoping to get pregnant with me. It seems like a cruel twist of fate to have your prayer answered, but with an asterisk. To have a daughter who grows up questioning the existence of God and falling for other women.

Family friends misspell my name. Teachers. Then women I think – wish – I meant something to. I take it as a valuable lesson, internalize every misplaced “i” and use it as a check on my own fantasies. See? They don’t care. Your name’s right in front of them, on their phone screen, but it’s too much effort for them to check. To revisit. I think about being a savior – how desperate my need is to be a comfort to someone who comforts me. I think about martyrdom – the way my mum called me a martyr every time I got swept up in sadness and started to punish myself for it, not knowing how else to react when it seemed like my pain was an unbearable disappointment I’d dropped at her feet. And what else did she expect from me? Kristen. The martyr. Kristen. The savior.

I know I should feel lucky. Somewhere between one and three percent of fetuses diagnosed with my condition survive until birth. The Turner Syndrome Society describes these babies as “miracles,” but how is anyone meant to live up to that label? A part of me feels like I need to earn – to justify – my very existence. Continuously. An ever-moving goal that I’m never going to reach, no matter how hard or how long I try. Because miracles shift, slip from your grasp as soon as they start to materialize. Turn into something you never wished for. I feel more like proof of that reality than any kind of lottery winner.

Lately, I’ve found my name harder and harder to say out loud. Coffee orders. Appointments. Introductions. I don’t know why it’s more difficult now, if I just didn’t notice the effort it took to make the sounds with my mouth and throat when I was younger or if my muscles and vocal cords have aged in such a way that it’s now a struggle to articulate. The second syllable gets swallowed, and I wonder if that’s how I like it. What I wish I could do physically, all the time. But the first half of my name is too sharp, too bold – it’s always going to be heard, even if the end trails off. Won’t let me hide. Makes me feel the need to apologize for its brashness.

And then, of course, it’s brittle, too. Can’t seem to withstand much at all.

I’m walking around my neighborhood, listening to MSNBC, when another segment about a woman who’s had to flee her state to get an abortion starts. I sigh. Simmer. Listen to Nicolle Wallace and try to psychologically absorb some of her strength. Feel like I’m achieving something just by listening. This is a woman who wanted her baby – nicknamed it Spooky because it was due on Halloween – and I cringe at my own splintered instincts, thought-processes: the false distinction between a “good” abortion (one that undermines every argument on the right) and one that’s less easily packaged for the media.

This woman – from Idaho – explains that she went in for an ultrasound and then discovered there was a chromosomal abnormality in the fetus. I wonder whether it could have possibly been Turner’s, then berate myself for making everything about my own experiences. Wonder at the irony. Then she says it – not Mosaic, but still missing x chromosomes. Fluid gathered behind the baby’s neck and all around the body. She went through the harrowing process of needing to wait – hope for – a miscarriage. An article in the Idaho Capital Sun describes the questions she and her husband had to ask themselves when she realized her body – and the fetus – were holding on. “Do we try? But for what purpose?”

I don’t know why I didn’t have fluid behind my neck – why I got to have two x chromosomes in most of my cells. Why this woman had to go through the process of fighting for an abortion. And I’m left wondering what sets me apart from the fetus she chose to save from pain.

My grandpa called me Spooky.

I’ve graduated past the worries of conceiving a child now. The word infertile was never used, but the gynecologist intimated as much when I got an ultrasound of my ovaries in my early twenties. I could have chosen to freeze some of my eggs a couple of years earlier, but I’d already discovered enough about myself at that point to know that there were too many additional factors at play – a future partner who might have a stronger desire to carry a child and a better chance of succeeding – for me to make such an extreme choice and risk the guilt of realizing, years or decades down the line, that it was all wasted time and energy and pain and money. I didn’t want to pick out a random sperm donor on my own – fertilized eggs have a better chance of surviving the deep freeze – and I didn’t even know if I wanted to have children. Would want to have children. If I’d ever be capable of teaching another human how to be a human being when I haven’t figured it out myself.

On a Facetime call with my mum last year, she asked when I was going back to see my endocrinologist. I’m on to my fourth one, now. Part of me feels like I need to stop moving and instead figure out what exactly I’m running from, leaving cities and countries and people behind again and again. Each new doctor wants new bone density scans because, apparently, each machine can vary slightly in its readings and it’s not ideal to compare scans from different locations. There’s a risk I might have the skeleton of a woman twice my age by the time I’m forty. But I’m not entirely sure that I’ll make it that far.

This decade of my life is when I’m most likely to experience aortic dissection – I had no idea, thought the echocardiograms I’d already gone through were enough to prove that my heart was in decent shape. That it could hold up. For now. But my mum brings up the risk – fuels a sense of existential anxiety that I don’t think I’ve ever experienced before. You should mention it to the endocrinologist, she says. Remind her. I do some Googling. Picture one of the walls of my heart gently fracturing and appreciate that my body’s failings – weaknesses – have a kind of romantic symbolism to them. Even if my name doesn’t.

November 19, 2024

Further considerations

Pray at the Altar of Delusion and Haiku Suite on the Nine Muses

Look upon the simple life tinged by shades of emotions, all // of it a facade to entertain one’s own delusions.

Someone Else's Grief and Job Before the Job

By Ace Boggess

I’ve never walked in driving rain // as she does now, the noise so sudden & // vast as to become its own silence.